Understanding Relative Return: A Comprehensive Guide

In this article, we delve into the concept of relative return, explaining what it is, how it’s calculated, and why it’s a crucial metric in investment analysis.

What is Relative Return?

Relative return is the return generated by an asset over a period of time compared to a benchmark. The relative return is the difference between the return of the asset and the return of the benchmark. Relative return can also be referred to as alpha in the context of active portfolio management. This can be contrasted with absolute return, which is a stand-alone figure that is not compared to anything else.

Relative return is important because it is a way of measuring the performance of actively managed funds, which are designed to outperform the market. In particular, relative return is a way of measuring the performance of a fund manager. For example, an investor can always buy an index fund that has a low management expense ratio (MER) and guarantees the market return. Relative return is the most commonly used measure of a fund manager’s performance.

Investors can use relative return to understand how their investments are performing relative to different market benchmarks. Similar to alpha, relative return is the difference between the investment return and the return of a benchmark. There are a number of factors an investor needs to consider when using relative return. Many fund managers who use relative return to measure their performance typically rely on established market trends to generate their returns.

How to calculate Relative Return?

1. Estimate the absolute return of the investment you want to analyze: The absolute return earned by an investment over a given period of time. It can be calculated as follows:

Absolute Return = (Current Value of Investment – Original Value of Investment) / Original Value of Investment

2. Calculate the benchmark return: Calculate the absolute return for the benchmark to which you want to compare your investment.

3. Subtract the benchmark return from the absolute return to obtain the relative return:

Relative Return = Absolute Return of Investment – Absolute Return of Benchmark

So if your investment grew from $1000 to $1200 in 12 months, your absolute return would be ($1200-$1000)/$1000*100, or 20 percent. If your benchmark (e.g., the S&P 500 Index) grew 12% over the same period, your relative return would be 20-12, or 8%. This means that your excess return relative to the index is 8%.

How to use Relative Return?

In summary, relative return is a valuable tool for investors and portfolio managers. It provides a measure of performance that takes into account the context of the market or sector in which an investment is made. By using relative return, investors can make more informed decisions and achieve better investment results.

Relative Return vs. Absolut Return

Absolute return and relative return are two ways to measure the performance of an investment or fund. Here’s how they differ:

Absolute return: This is simply what an investment or portfolio has earned over a period of time. For example, if you invest $1000 in a stock and after one year your investment is worth $1200, your absolute return is $100 (or 20%).

Relative return: This is the difference between the absolute return and the performance of the market (or other similar investments) as measured by a benchmark, such as the S&P 500. For example, if your stock had an absolute return of 20%, but the S&P 500 (the benchmark) returned 12%, your relative return would be 8%. This means that your stock outperformed the market by 8%.

Investment strategies that aim to achieve a better Relativ Return

1. Relative value strategies: These strategies seek to take advantage of temporary differences in the prices of related securities. A common strategy is called pair trading, which consists of initiating a long and short position in a pair of assets that are highly correlated, such as a company’s common and preferred stock.

2. Long-only strategies: These involve taking long positions in stocks that are expected to outperform the benchmark. These strategies typically focus on security selection, sector allocation, or other tactics to generate excess returns over the benchmark.

3. Market Neutral Strategies: These strategies seek to eliminate market risk by taking equal long and short positions in different securities within the same market. The goal is to benefit from the relative performance of these securities to generate a better relative return.

4. Factor-based strategies: These strategies involve selecting securities based on certain characteristics or “factors”. Common factors include size, value, momentum, quality and liquidity.

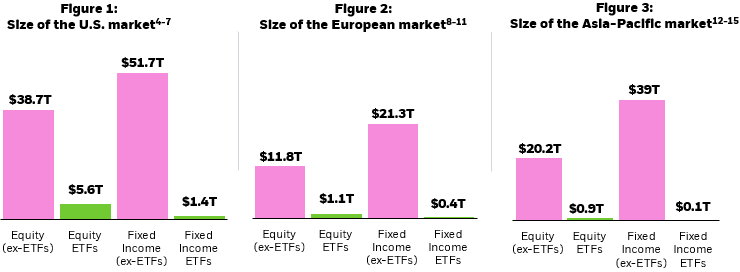

S&P 500 vs. Nasdaq Relative Return Comparison

S&P 500 vs. Nasdaq Chart

Both the S&P 500 and NASDAQ faced declines in the early 2000s due to the dot-com bubble burst, with NASDAQ seeing more significant losses. Before the 2008 financial crisis, both indices gradually recovered. However, during the crisis, they experienced substantial downturns. Following the 2008 crisis, both indices entered recovery phases. From the 2010s to 2020, the tech sector’s dominance drove NASDAQ’s significant outperformance compared to the S&P 500.

S&P 500 vs. Nasdaq Relative Return

Another approach to calculate the relative return difference involves dividing the return of one asset by the return of another asset. This division yields a numerical ratio that assesses the comparative performance of the two assets over a specified time period. A ratio greater than 1 indicates that the first asset outperformed the second, while a ratio less than 1 suggests that the second asset outperformed the first. This ratio offers valuable insights into their relative performance during the chosen time frame.

Visualize the S&P 500 and NASDAQ’s relative returns from 2000 to 2020, showcasing key market dynamics during this transformative two-decade span.

Early 2000s (Dot-Com Bubble Burst): In the early 2000s, both the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ experienced significant declines in response to the bursting of the dot-com bubble. The technology-heavy NASDAQ experienced more pronounced losses during this period. The chart shows the superior relative return of the S&P 500 over the NASDAQ during this period.

Global Financial Crisis (2008): During the global financial crisis of 2008, both indices experienced significant declines as the crisis impacted various sectors of the economy. The S&P 500, which represents a broader range of industries, also experienced significant declines on par with the NASDAQ, which is represented by the flat line of the relative return line.

Recovery and growth (after the 2008 crisis): Following the crisis, both indices embarked on a path of recovery and growth. Technology companies played a significant role in driving the NASDAQ’s performance, while the S&P 500 showed steady but moderate growth as the broader economy regained strength. This is reflected in the slow decline in the relative return.

Limitations and Considerations of Relative Return

While relative return is a valuable metric for evaluating investment performance, it’s important to recognize its limitations. One important consideration is that relative return alone doesn’t provide a complete picture of an investment’s performance. Here are some important factors to consider:

- Benchmark selection: The choice of benchmark can have a significant impact on the interpretation of relative return. Different benchmarks represent different market segments or asset classes. Therefore, it’s important to select a benchmark that is relevant to the investment objectives and asset class. The use of an inappropriate benchmark may distort the assessment of performance.

- Market conditions: Relative returns are highly dependent on market conditions. During bull markets, many investments tend to outperform their benchmarks, while bear markets can result in underperformance. Therefore, a single period of relative outperformance or underperformance may not be indicative of long-term success.

- Risk and volatility: Relative return doesn’t take into account risk or volatility. An investment that generates a higher relative return may also be associated with higher volatility and risk. Therefore, investors should consider risk-adjusted measures such as the Sharpe Ratio to assess whether returns are commensurate with the level of risk taken.

- Time horizon: The time frame over which relative returns are measured can greatly affect the results. Short-term fluctuations can obscure the long-term performance of an investment. It’s important to consider the time horizon of the investment and match it to the appropriate benchmark for a more accurate assessment.

- Diversification: Relative return does not capture the benefits of diversification. A well-diversified portfolio may not always outperform its benchmark, but it can provide a smoother and more stable investment experience, which may be more appropriate for certain investors.

Real-world applications of Relative Return

To illustrate the practical application of relative return, consider the following examples:

- Active vs. Passive Management: Relative return is often used to evaluate the performance of actively managed funds versus passive index funds. An investor evaluating an actively managed fund can use relative return to determine whether the fund’s higher fees are justified by its ability to outperform the benchmark.

- Portfolio construction: Asset managers and financial advisors use relative return when constructing portfolios for their clients. They seek to balance investments that have historically provided higher relative returns with those that provide stability and risk mitigation.

- Asset allocation: Asset allocation decisions are influenced by relative return. Investors may allocate more capital to asset classes or sectors that have demonstrated consistent relative outperformance over time.